The stakes are high and students, already under immense pressure, can afford little to no space for linguistic deviations.

#Japan monolingual country series

The dreaded ‘exam hell’, a series of standardized examinations that Japanese students must take during their entire school lives, require mastery of the standard language as well as being able to produce it as part of an appropriate repertoire. However, it is not all fun and games as the necessity to confront the demands of standard language remains, and most young Japanese students know this well. In real life, too, dialects enable people who do not wish to fit within mainstream language practices to inhabit a different ‘voice’, performing what has been called ‘ dialect cosplay’ as an act of linguistic transgression.ĭialects may seem to assume playful roles in many occasions. Dialects are also used to portray characters in media for their ability to convey the stereotypes associated to them.

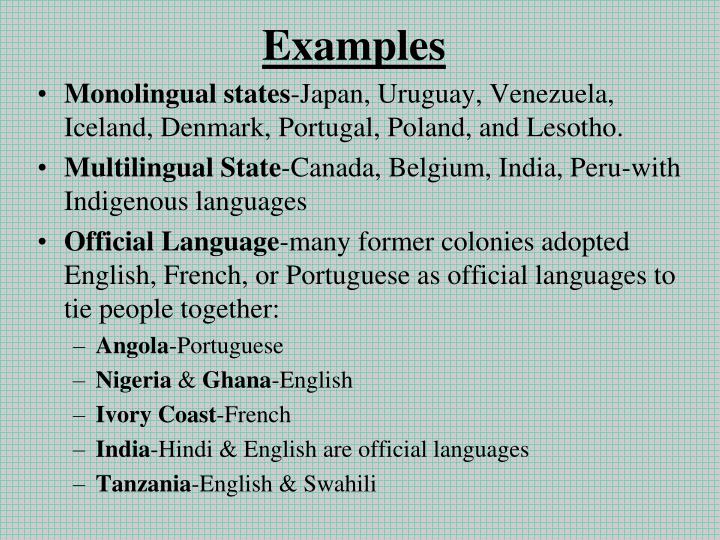

The linguistic and cultural distance between center and periphery has been turned into a marketable commodity. Sometimes grammar rules and words are turned into anthropomorphic characters and appear on souvenirs and merchandise like the notebook I have received at the University of Kōchi during my time there as an exchange student. Institutional bodies such as museums and tourism boards use dialects as a means to promote local culture. This role has been embraced by prefectures and individuals alike. Other varieties saw their usage severely curtailed, starting in schools which tried to stamp out anything other than Tōkyō Japanese.ĭiscouraged in official communication, dialects have become an expression of locality, part of the cultural identity associated with a specific place. Therefore, all the other ways of speaking throughout the Japanese archipelago were categorized as dialects. Communications in Japan have indeed been standardized, and Japan’s literacy rate is as high as 99%, one of the highest in the world. To achieve that, the Tōkyō variety (or “Edo”, as Tōkyō was called until the late 19 th century) was chosen as the base to envision a ‘national language’ 国語 kokugo.ġ50 years on and the political efforts that have been made to establish a common language can be considered largely successful. Its goal was to replace older forms of the Japanese language with the vernacular variety of the time to facilitate literacy. Tōkyō has had a decisive impact on the ‘movement for the unification of the written and spoken language’ 言文一致運動 genbun itchi undō. Given its importance, it is not surprising that the city has had a central role in issues related to language as well. Our journey starts from the capital Tōkyō, the city that hosts the majority of the financial and political institutions of the country. On our journey, we will see how linguistic resources change value, function and ownership as they move through an ideologically stratified system where the norms and criteria of appropriateness that emanate from the center influence those of peripheral and liminal territories. This post explores Japan’s linguistic ecology by exploring the relationship between center and periphery. This is not true and Japan is a multilingual and multicultural country where varied languages and traditions coexist. Japan is often erroneously perceived as a monolingual country. The cover also features popular landmarks of the prefecture.

“The Tosa dialect is fun!!” Notebook with characters representing the grammar of Tosaben, the dialect of the Kōchi prefecture in Shikoku.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)